This is a transcript of this video.

The bibliography for this episode can be found here.

For the audio podcast version click here on a mobile device.

Hello fellow kids and welcome back to What is Politics.

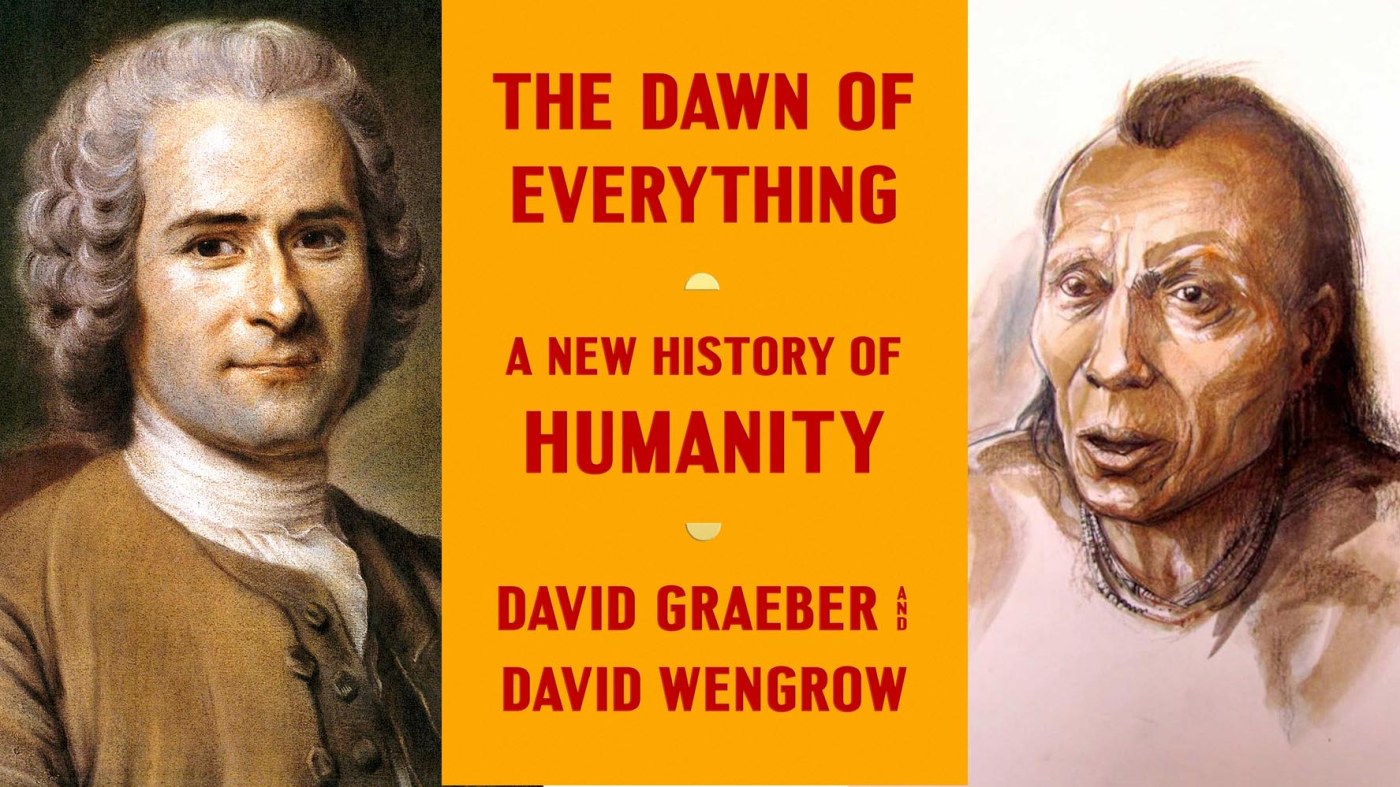

In this episode we’ll be covering the rest of Chapter 3 from David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything book, which is entitled Unfreezing the Ice Age.

In this part of the book, the authors try to argue that human societies used to shift back and forth from hierarchy to equality for fun, play and expedience, which leads them to the big thesis question of the book: if societies in the past used to shift back and forth from hierarchy to equality seemingly at will, then how is it that for the past several thousand years, most societies seem to be stuck in hierarchy.

Before we get in to the text, let’s do a little recap of some of the important theory points that we’ve been making in this series so we can understand what we’re reading, and also so that we can understand what’s going on in the world around us.

As discussed in earlier episodes, the word politics refers to decision making in groups – which includes the state, but also any group, the workplace, the family, your basketball team.

So, when we’re talking about hierarchy or equality in a political context, what were talking about is hierarchy or equality of decision making power. Does everyone have the same power, or do some people have more power than others – and if so, what’s the basis of the inequality of power, and what are the moral or intellectual justifications for it – because inequalities of power always come with justifications of some sort – efficiency, merit, superiority, human nature, divine providence, being the vanguard of the working class.

And whatever the justification is clearing out space for the master race, or creating the necessary conditions for socialism – any argument that justifies a political hierarchy is by definition a right wing argument.

Because in politics the left refers to the people who support equality of decision making power, and the right refers to those who support hierarchies of decision making power.

And last time, we looked at the difference between dominance hierarchy, where the hierarchy is benefits the people on the top of the hierarchy, and imposed by them, vs. a democratic hierarchy where the hierarchy is formed for the benefit of its members, and where the people on top, only get to be there insofar as they benefit the rest.

In the future and we’ll look at how democratic vs dominance hierarchy is a spectrum, and how democratic hierarchy can morph into dominance hierarchy in the right circumstances – or rather the wrong circumstances – but what we need to understand today, is that while people might choose to establish a democratic hierarchy in order to achieve shared goals for the sake of efficiency, the idea that a society as whole would choose to establish itself as a dominance hierarchy does not make any sense. Dominance hierarchies are chosen by people on top choose it, and imposed on the people on the bottom, who at best tolerate it for lack of better options. And the level of dominance hierarchy is determined by the relative bargaining power of the two parties of classes.

Now, because people don’t choose to be stuck in dominance hierarchy on purpose – the existence of a dominance hierarchy can only be explained by particular circumstances which give some people certain bargaining power advantages over others.

And we saw that there’s basically only one general recipe for all dominance hierarchies – 1st, you need to have some people who are able to control access to resources that other people need – and 2nd, you need for there to be no preferable alternatives to get those resources other than to subject yourself to the commands of the people who control those resources.

So, if we want to answer Graeber and Wengrow’s question of how we got stuck in hierarchy – meaning if you want to understand where a particular dominance hierarchy comes from and how to get rid of it, or how to reduce it’s severity, then first you need to ask “what are the conditions that are giving some people the ability to impose their choices on other people”. And then once you’ve identified those, the next thing you need to ask is “what can we do to change those conditions in a way that reduces or eliminates those advantages”.

Unfortunately, as Graeber and Wengrow will later tell us in Chapter 5, they explicitly don’t want to think about conditions or circumstances. Instead, they want to focus on conscious choice and “freedom”. And the reason for this, is because they mistakenly think that if conditions are what result in hierarchy or equality, then this means that we are truly stuck forever stuck in hierarchy today because of the conditions inherent to advanced industrial civilization. And they quote Jared Diamond and others to that effect in chapter 1.

But what the authors forget as they go down this dead-end path of seeing hierarchy as a random choice disconnected from conditions, is that one of the powers of human beings is that we have the power to choose to shape and change the conditions that we live in – at least sometimes – it all depends on the conditions!

Unfortunately, as a result of trying to avoid materialist answers, and of trying to focus on discombobulated conscious choices outside the context of the conditions in which those choices are made, not only are the authors unable to answer their own questions, but they routinely bury or ignore all of the parts of the sources that they discuss which actually do answer those questions, which we saw last time and which we’ll see more of today.

Materialism and agency are not opposed to eachother – materialism is simply the context in which freedom and choice are exercised. And without it we throw away our best tools for understanding why people make choices, or for predicting what choices they will make, which makes it impossible to design institutions and rules that will have the effect we want them to have.

OK, so now let’s get into the book, and let the cartoon, begin:

CHAPTER THREE

So this part of the chapter starts off with some intellectual history:

The authors point out that in the ancient world – philosophers from greece to india to chiner took it for granted that we only really think when we dialogue with others, and that this is why so many philosophical works are written as dialorgs instead of just monolorgs. Individual consciousness on the other hand was something that was exceptional and the result of a life of contemplation and studying.

“Humans were only fully self-conscious when arguing with one another, trying to sway each other’s views, or working out a common problem. True individual self-consciousness, meanwhile, was imagined as something that a few wise sages could perhaps achieve through long study, exercise, discipline and meditation. What we’d now call political consciousness was always assumed to come first.

But then in europe with the enlightenment, intellectuals got all of this backwards. Because they saw europe as waking up out of 1000 years of lack of superstition and rigid religious dogma, european philosophers assumed that ordinary people could have individual consciousness but politically they would traditional people just blindly followed traditions and that political consciousness wasn’t possible until civilization and literature and enlightenment made it possible, and that it was only available to the educated and well read.

> All this would have come as a great surprise to Kandiaronk, the seventeenth-century Wendat philosopher-statesman whose impact on European political thought we discussed in the previous chapter. Like many North American peoples of his time, Kandiaronk’s Wendat nation saw their society as a confederation created by conscious agreement; agreements open to continual renegotiation.“

OK so far so good, as far as I know since I have no knowledge of this field – but then the authors come back to their condescending misrepresentations about the anthropology hunter gatherers:

“Scholars still write as if those living in earlier stages of economic development, and especially those who are classified as ‘egalitarian’, can be treated as if they were literally all the same, living in some collective group-think: if human differences show up in any form – different ‘bands’ being different from each other – it is only in the same way that bands of great apes might differ. Political self-consciousness, or certainly anything we’d now call visionary politics, would have been impossible.”

As usual on this subject, the authors are arguing with scholars from the 1970s or before that. Scholars no longer write like that, unless they’re discussing the entire palaeolithic era in like 2 pages in order to make a larger point about something else, because you can’t make generalizations or discuss giant periods of time in any other way.

But then as they do so many times in this book, they try to have it both ways:

“Now, admittedly, there have always been exceptions to this rule. Anthropologists who spend years talking to indigenous people in their own languages, and watching them argue with one another, tend to be well aware that even those who make their living hunting elephants or gathering lotus buds are just as sceptical, imaginative, thoughtful and capable of critical analysis as those who make their living by operating tractors, managing restaurants or chairing university departments.”

Newsflash: Anthropologists who spend years talking to indigenous people in their own languages is literally every cultural anthropologist with a PhD – that is how you get your PhD. The authors are trying to make it seem like there are these good anthropologists who humanize the subjects of their research, but then there are all these bad anthropologists who believe in egalitarian origins and make generalizations about cultures – but in the real world, these are usually the exact same anthropologist doing both of these things!

When you write an ethnography, you will tend to write a lot of individualized stories about all the people you lived with for the years you spent there. But then if you’re the exact same person and you go and write a book about anything involving about humanity as a whole – like human origins, or the evolution of violence, or the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture – you’re going to talk mostly in generalizations, and in ways that erase individuality because you can’t talk about these topics in any other way!

For the authors to chastise people for this is like getting mad at someone who takes a picture of the earth from outer space for erasing individual human identities – it’s just nonsense – and it’s crippling nonsense, preventing us from being able to actually do anything useful with anthropology.

It’s also extremely ironic because earlier the authors were chastizing anthropologists for not having the courage to make any generalizations! Apparently generalizations are only permitted if you make the types of generalizations that the authors like.

The authors then go on to point out that in many traditional societies, eccentric and nonconformist people are not punished for deviating from social norms, but instead they’re often revered or celebrated in different ways.

And they go on to talk about how in times of crisis, the Nuer pastoralists in southern Sudan will often elevate people who would be considered insane or schizophrenic, and follow them as prophets.

“a person who might otherwise have spent his life as something analogous to the village idiot would suddenly be found to have remarkable powers of foresight and persuasion; even to be capable of inspiring new social movements among the youth or co-ordinating elders across Nuerland to put aside their differences and mobilize around some common goal; even, sometimes, to propose entirely different visions of what Nuer society might be like.”

Now this is correct, and super interesting – but what would have been more interesting and more useful would have been for them to talk about how these Nuer bipolar prophets aren’t just randomly proposing different visions of what Nuer society might look like. They’re fulfilling a specific social function, in response to particular conditions, as others have historically done in similar conditions.

The whole phenomenon of crazy prophets in Nuer society seems to be recent phenomenon – starting around the turn of the 20th century. And according to E Evans-Pritchard who wrote the classic studies of the Nuer in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, Nuer prophecy began as a response to war and aggression from the outside, which required the Nuer, who are a male egalitarian tribal society, with no political leaders and no formal organization beyond the tribal level, to organize massive coordinated responses to colonial invaders and other people encroaching on their territories.

So the reason that people suddenly started following anomalous weirdos who don’t conform to social norms, is because these people allowed the tribes to coordinate under leadership in ways that couldn’t otherwise have existed within the confines of their existing social structure. If you elevated a regular person to a special leadership status, it would disrupt the whole existing social order and create disruption and conflict. But you could elevate a weirdo person who was already outside the norms of the existing society and existing politics without threatening the fiercely egalitarian power balance between men in Nuer society.

Evans-Pritchard also noticed that the Nuer culture as a whole had many similarities to the ancient israelites in the early parts of the old testament, including the prophetic tradition. The ancient israelites were nomadic pastoralists just like the nuer with similar a social and political structure at that point in time, and the early biblical prophets emerged in similar circumstances: in order to unite independent competing tribes in order to fight wars in a system that allowed for no higher political authority beyond the male head of the family.

Monotheism is thought to have emerged for related reasons, as a locus to unite the different competing tribes with different identities into one political group versus others. And Evans-Pritchard noted that monotheistic ideas were gaining traction among the Nuer and spread by some of their recent prophets as well, apparently for similar reasons.

The authors are hinting at when they talk about prophets allowing the Nuer to imagine new forms of social organization, but I think they left out all of this context for a reason – because it highlights just how important conditions are – to the extent that people 5000 years apart in time, living in totally different worlds, from different racial, religious and ethnic groups, end up making very similar choices in similar circumstances.

NAMBIKWARA

OK, so now the authors try to push their conscious choice theory by talking about three cultures that change their social structures seasonally – or do they?

First they talk about the Nambikwara, who are an amazonian people who according to Claude Levi-Strauss, do horticulture in the rainy season for about 5 months, and then do hunting and gathering in very difficult conditions for the rest of of the year.

And the first point that the authors try to make here is that the Nambikwara don’t fit into the supposedly rigid evolutionary models of behavioural ecologists / materialist anthropologists who divide people up into artificial categories like hunter gatherers and horticulturalists and pastoralists and sedentary farmers. Supposedly these anthropologists heads would just explode at the idea of a culture that goes from one mode of production to the other seasonally, and the authors seem to be implying that we should stop using these types of categories altogether.

As proof that these categories are useless as is all of materialist anthropology, the authors tell us that not only do the Nambikwara change economic activities from season to season, but that they also change their social structure, telling us that their chief has much more power and authority in the foraging season than he does in the horticulture season, which according to the authors is the opposite of what materialist behavioural ecology models tell us. Apparently in the 2 dimensional 1960s caricature that Graeber and Wengrow paint of modern anthropological theory, hunter gatherers are all supposed supposed to be egalitarian, and farmers are all supposed to be hierarchical – which of course is strawman nonsense, there are plenty of hierarchical foragers and plenty of relatively egalitarian horticulturalists which anthropologists have been discussing since the 19th century – remember that Marx and Engels’ discussion of primitive communism was based on the Haudenosaunee horticulturalists.

And on top of that, the authors also tell us that Nambikwara chiefs act like modern welfare statesmen redistributing wealth to the poor just like we see in our big industrial civilizations. So Boom, there are no categories! Take that the stages of history theory, even though stages of history theories have already been dead for several decades already!

All of this is why anthropology has supposedly ignored the Nambikwara and all of the lessons they can teach us about agency and freedom and political consciousness blah blah blah.

Now there is such a mess going on here, that it’s hard to untangle it – and my head is still spinning from just how bad it was which sucked up an enormous amount of time out of my life as I kept getting sucked deeper and deeper into a swirling vortex of total nonsense and awful scholarship.

I was originally going to read the authors sources and then give materialist explanations for the seasonal differences in Nambikwara social and political structure – but that turned out to be impossible.

The authors tell us that:

“Chiefs made or lost their reputations by acting as heroic leaders during the ‘nomadic adventures’ of the dry season, during which times they typically gave orders, resolved crises and behaved in what would at any other time be considered an unacceptably authoritarian manner; in the wet season, a time of much greater ease and abundance, they relied on those reputations to attract followers to settle around them in villages, where they employed only gentle persuasion and led by example to guide their followers in the construction of houses and tending of gardens. In doing so they cared for the sick and needy, mediated disputes and never imposed anything on anyone.”

But Levi-Strauss doesn’t say anything like this at all. According to Levi-Strauss the chief had no coercive authority and that his only power was persuasion – all year round. If anything you could read into Levi-Strauss that the chief had less authority in the hunting season because if he didn’t do a good job people would just leave and join a different band to the point where he could actually lose his position, but he doesn’t say anything specifically about changing levels of authority from season to season anywhere in his texts on the Nambikwara.

It seems like the authors just made this stuff up about the chief being authoritarian in the hunting season, in order to make it seem like the Nambikwara had two different political systems and that scarecrow strawman anthropologists are wrong about hunter gatherers always being egalitarian.

I’ll include the relevant parts of the Levi-Strauss text in the transcript, because I had originally included a whole section comparing the two Graeber & Wengrow texts to the Levi-Strauss text – but then just before recording, I found out the Nambikwara don’t actually even switch from hunting and gathering to farming to begin with!

David Price and Paul Aspelin who independently of each other each lived with the Nambikwara for years at a time in the 1970s, both confirm that the Nambikwara do not actually switch from nomadic foraging in one season to sedentary farming in the other season. And Aspelin found that this was also the case in Levi-Strauss’ time as well. Apparently Levi-Strauss only stayed with them during an extended hunting expedition and had misunderstood this to be the way of life for 7 months out of the year. And he had never even visited a village.

So while I can’t give materialist explanations for things that don’t exist, what I can do is point out that the authors’ war on categories is completely insane. It’s this very typical post-modern brain disease where you start with an important and valid critique – that categories are artificial constructs, not fixed realities – but then, instead translating that into constructive lessons they just go straight into throw the baby out with the bathwater mode – eliminate all categories – each individual tree is different! There are no species! Spruce trees are a social construct!!

And the result is that if you take this garbage seriously, it prevents you from being able to apply knowledge in any practical way. All categories of things that exist in the real world – even things like fruits vs vegetables, arms vs wrists, berries vs citrus fruits, or man vs woman as is topical nowadays – these categories are all imperfect and they break down at a certain point. But we use them anyways, because they are short cuts that prevent us from having to re-invent the wheel every single time we encounter things.

Like good luck figuring out which wood to use if you want to building a house if you don’t know the difference between a pine tree and a douglas fir! Or imagine trying to be a surgeon if you refuse to acknowledge that a heart and stomach are separate organs because there’s no exact way to tell where one ends and the other begins and all the organs are actually interconnected and work as one big system! It’d be like being paralyzed on mushrooms staring at the ceiling.

This is why academia has turned into a giant masturbation festival since post-modernist paradigms took over. Jizzle jizzle jam!

The reason that we create subsistence categories in anthropology – like foragers, pastoralists, horticulturalists – immediate return vs delayed return foragers – is because those subsistence practices tend to create conditions which have important and specific consequences on culture and political structure and ideology etc.

For example, as I’ve mentioned before, immediate return hunter gatherers are almost always hyper egalitarian – while hunter gatherers who focus primarily on fishing are usually very hierarchical.

And crucially to the authors’ thesis questions about how do we get stuck in hierarchy – having these kinds of categories helps you isolate the causes of patterns and similarities that you find within those categories. What is it about nomadic pastoralism that always results in male dominance and cultures with lots of blood feuds and honour codes? Why are people in horticultural societies so often obsessed with accusing eachother of witchcraft? Why is it that immediate return foragers never seem to care very much about witchcraft or to get caught up in blood feuds?

And we have a lot of very good answers to these types of questions, but you’ll never learn about them from Dawn of Everything, because the authors heads are buried too deep in their own bunguses, wanking on about freedom and choice totally out of context of the practical conditions that those choices are made under.

One of the main effects of post structuralist turn in academia – where you attack anyone who does any generalizing or who looks for materialist answers to things or who even uses categories – is that humanities academia is no longer oriented towards producing anything that can actually help anyone do anything to change society. You can’t even take the first step of asking why anything happens. You can ask who what where and when, but if you ask why, that inevitably leads to materialist inquiries, and suddenly everyone gets really uncomfortable like you made a big stinky and then they start accusing you of essentialism and objectifying people and whatever other nonsense.

What started as a well intentioned critique of anthropology’s role in helping powerful institutions destroy traditional cultures for profit, turned into a formula for utter paralysis. And this is one of the main reasons why postmodernism is so popular in elite academia – because it totally neutralized the threat to power that started to emerge in the 60s and 70s as working class people entered the university system because of the G.I. bill.

So where anthropologists in the 70s used to want to want to learn from different cultures in order to figure out how to make the world a better place, today if you have an anthropology degree, unless you up becoming a professional masturbator your most likely job prospect is helping advertisers figure out how to make women in Mauritaria feel like they’re too fat. “Hey Senegalese mom – does your baby suffer from premature baldness? Give your 2 month old a normal life and a full head of elvis hair, with ro-goo-goo-ga-ga-gaine”

And ironically, although Graeber was critical of post-modernism, and although he and Wengrow wrote this book because they want to encourage us to change our society, Dawn of Everything very much contributes to these awful trends.

In Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, David Graeber wrote “

“In many ways, anthropology seems a discipline terrified of its own potential. It is, for example, the only discipline in a position to make generalizations about humanity as a whole … yet it resolutely refuses to do so.

And that’s exactly right, but unfortunately, in this book they’re lobbing attacks that if taken seriously, would make it impossible to make generalizations!

Now, if we read the work of authors who actually lived with the Nambikwara, we can see that there are differences of power in chiefly authority – not between different seasons, but rather between different chiefs in different regions of nambikwara territory.

David Price did a study of 70 nambikwara leaders and in his article he found that 61 of the chiefs almost never told anyone what to do at all. They led entirely by example.

“The typical leader begins making a garden and other men join him; he announces his intention to hunt peccary and other men go along

The chief’s authority is so nonexistent that Price suggests that maybe he shouldn’t even be thought of as a chief, but more of as a respected elder brother member of his band, which he often literally is, of the type you often find in hyper-egalitarian immediate return societies.

Now the other 9 chiefs still had no enforcement power, but unlike the other chiefs they did actually issue commands and tell people what to do. And all of these more “authoritarian” style chiefs all lived in a northern area where the Nambikwara were frequently under attack which creates conditions which Price believes was the reason why people in those groups tolerated being given orders.

Anyways Graeber and Wengrow continue:

“What impressed Lévi-Strauss above all was [the Nambikwara’s] political maturity. It was the chiefs’ skill in directing small bands of dry-season foragers, of making snap decisions in crises (crossing a river, directing a hunt) that later qualified them to play the role of mediators and diplomats in the village plaza. But in doing so they were effectively moving back and forth, each year, between what evolutionary anthropologists (in the tradition of Turgot) insist on thinking of as totally different stages of social development: from hunters and foragers to farmers and back again.

Ugh – so now the authors are pretending that we’re in not just stuck in the 1950s, but more like the 1850s. No one believes that foraging or farming are different “stages of development anymore”. They are different adaptations to different conditions. There are all sorts of examples of people who quit farming and become foragers, or pastoralists, or back and forth and around.

In the 19th century you had the classic idea that Turgot first proposed, but was most famously articulated by Lewis Henry Morgan, that you had these stages of development where people moved from the worst, hardest form of economy – hunting and gathering, up to better and better ones, pastoralism and then horticulture and then farming and then awesome civilization – or as morgan put it savagery, barbarism and civilization, with different substages for each – lower savagery, middle savagery, higher savagery, etc.

Although Morgan actually had enormous respect for the native american people that he lived with, there was a clear implication in his scheme that societies were advancing up the ladder of progress to becoming awesome civilized gentlement with big sideburns, stiff upper lips and extreme constipation issues.

These theories fell out of favour after WWII and the rise of anti-colonialism and civil rights stuggles, but they revived in a very different form in the late 60s and 70s after the man the hunter conference, because people became interested again in how we went from equality to hierarchy. And so, you the birth of modern social evolution theory.

But in this version of social evolution is not about stages and progress from worse to better or from simple to complex, it’s about adaptation to conditions – just like biological evolution theory. And people don’t talk about this anymore, but it’s always been a staple of anthropology that the whole reason humans have such extensive cultures is precisely to adapt to our environment and our circumstances.

So cultural evolution could mean going from a simple social structure to a more complex one, because you can’t get to complexity without building from less complex stages – like you can’t build a car without first having invented wheels, and oil extraction and metalsmithing first – but it could also mean becoming more simple, like going from stratified agricultural society with hierarchy and specialization to a pastoralist or hunting and gathering society, which various societies have done, like the Lakota that we’ll talk about in a bit.

Any lingering ideas of social complexity equating with progress fell apart when we realized in the late 1970s that moving from hunting and gather agriculture almost always resulted in going down the ladder in terms of quality of life!

Mark Nathan Cohen found that most societies that adopted agriculture for the first time, did so out of desperation, and that health measures decreased drastically after the transition! And Marvin Harris one of the big Materialist anthropologists of the 70, 80s and 90s found that every major increase in technological and social complexity was actually adopted out of desperation, and that people’s lives at first got worse each time, and that it was only worth it because the alternatives were even worse.

And then the authors make some more stuff up:

“Although Lévi-Strauss went on to become the world’s most renowned anthropologist and perhaps the most famous intellectual in France, his early essay on Nambikwara leadership fell into almost instant obscurity. To this day, very few outside the field of Amazonian studies have heard of it.

David Price, on the other hand, writing in 1980 when social evolutionism was going strong, tells us that the exact same article has

“a central place in the literature of comparative politics. It has become a classic study in primitive leadership, assigned to students and cited in other articles whenever an example of the world’s simplest political institutions is called for.”

And he points out that the article had been reprinted in three different versions in Levi-Strauss books, plus in a major anthology on comparative political systems that came out in the late 1960s.

And the article is still cited in our times – for example, as I was trying to figure out what the story was with Nambikwara chiefs I found Levi-Strauss’ article referred to several times in an article on political leadership from 2015. And the psychology leadership was the focus of the article – not the stuff about the seasonal changes that he got wrong and that Graeber and Wengrow got double wrong in Dawn of Everything.

Anyhow, so here we get to one of the many parts of the book that make me vewy vewy angwy:

“One reason [for why Levi-Strauss’ article disappeared] is that in the post-war decades, Lévi-Strauss was moving in exactly the opposite direction to the rest of his discipline. Where he emphasized similarities between the lives of hunters, horticulturalists and modern industrial democracies, almost everyone else – and particularly everyone interested in foraging societies – was embracing new variations on Turgot, though with updated language and backed up by a flood of hard scientific data. Throwing away old-fashioned distinctions between ‘savagery’, ‘barbarism’ and ‘civilization’, which were beginning to sound a little too condescending, they settled on a new sequence, which ran from ‘bands’ to ‘tribes’ to ‘chiefdoms’ to ‘states’.

“The culmination of this trend was the landmark Man the Hunter symposium, held at the University of Chicago in 1966. This framed hunter-gatherer studies in terms of a new discipline which its attendees proposed to call ‘behavioural ecology’, starting with rigorously quantified studies of African savannah and rainforest groups – the Kalahari San, Eastern Hadza and Mbuti Pygmies – including calorie counts, time allocation studies and all sorts of data that simply hadn’t been available to earlier researchers.

So for all those assholes on twitter and youtube screaming at me that the authors aren’t against materialism, and that I’m strawmanning them and that they’re only attacking popular writers, not real anthropologists – behavioural ecology IS materialist anthropology. It’s the people who try to explain the behaviour of human societies by understanding the environments and practical circumstances that we live in. It’s where you find any serious scholar who’s interested in figuring out what causes societies to be hierarchical or egalitarian or what causes just about anything that people. It’s exactly what the authors should be doing, yet it’s the target of their constant derision.

And like I’ve been talking about throughout these book critique episodes, Man the Hunter is the conference that introduced anthropology and the popular reading public to the fact that hyper egalitarian and free societies actually exist. Democratic, gender egalitarian, anarcho-communist societies without political authority or gerontocracy, and without organized warfare. Things that Graeber and Wengrow should be deeply interested in, but that they insist on ignoring, or else attacking and dismissing.

This conference happened right at the apex of the cold war, when we were being told that you can either have equality or freedom, but you can’t have both – and that equality is simply against human nature and that any attempt to create an equal world will result in the horrors of stalinism or the terror of the french revolution. These are ideas that are still deeply, deeply ingrained in our minds – like listen to any Jordan Peterson lecture where he’s freaking out about the left and the cultural marxists, or any Praeger U video – this is where they’re coming from.

This conference showed the world that not only can you have both equality and liberty, but that it was quite possible that most human beings were organized along libertarian and egalitarian lines for 90+% of our existence as a species – after all, human beings were all hunter gatherers until 12,000 years ago, most hunter gatherers are at least male egalitarian, and most foragers who practice the simplest type economy that our earliest ancestors probably practiced are hyper egalitarian with gender equality.

The political implications of this were enormous and left wing anthropologists jumped on it, while those inclined to the right had a tantrum and tried their best to dismiss and downplay it, much like Graeber and Wengrow do in this book, albeit for different reasons. Tellingly, the broader political left which was more interested in authoritarian types of socialism just ignored it, as did the broader political right and mainstream for obvious reasons – kind of like everyone just ignored what the anarchists accomplished in the spanish civil war until Noam Chomsky focused attention on it in the 1990s. And as a result, outside of a brief flash, knowledge of this stuff has never really filtered into the general culture or even our political culture which is something that I’m trying to correct with this series.

Whereas for left wing anthropologists stuff was a revelation, for Graeber and Wengrow this conference was just a giant festival of infantilizing hunter gatherers:

“The new studies overlapped with a sudden upswing of popular interest in just these same African societies: for instance, the famous short films about the Kalahari Bushmen by the Marshalls (an American family of anthropologists and film-makers), which became fixtures of introductory anthropology courses and educational television across the world, along with best-selling books like Colin Turnbull’s The Forest People.

Aha! … Colin Turnbull’s the Forest People. This is all just speculation, but to me this one book just might be the key to understanding Graeber’s lifelong demented attitude towards hyper egalitarian societies and his belief that the theory of egalitarian ancestors by definition implies infantilism.

The Forest People is a book written in 1961 for a popular audience about the Mbuti hunter gatherers of the Ituri rainforest in central africa. The Mbuti are one of those immediate return, hyper egalitarian, gender egalitarian societies – and even as hyperegalitarian societies go, they’re one of the most hyperegalitarian, where women hunt together with men and even older children often can make decisions that trump the will of the adults if it’s something that will affect the future of the group, when todays kids will be tomorrow’s adults.

And much like Graeber and Wengrow are doing with Dawn of Everything, Turnbull wrote The Forest People for a popular audience with a particular message in mind – in Turnbull’s case, the message was that human equality and freedom are possible and that we have a lot to learn about these things from societies like the Mbuti.

And because Turnbull was trying to get that message across, and because the book was written for popular consumption and because it was 1961, the Forest People reads a bit like a fairy tale. And it doesn’t exactly ignore the various problems or difficulties of Mbuti life at the time, but it does portray mbuti society a bit like a happy harmonious smurf village.

So because of the romanticization, and also I guess becauase the Mbuti are a pygmy people, who are an average of 4’11” tall – a modern reader, might feel like the Forest People is infantilizing the Mbuti. And I can see why Graeber might react negatively to this book, and also to the annoying hippie professors and others who glommed onto it as an example of our inherent Rousseauian smurfy good nature, polluted by civilization etc.

To be honest, for it’s various flaws, the Forest People is what got me into anthropology and I think that Colin Turnbulls work is really amazing in terms of describing how the material circumstances of Mbuti life vs the circumstances of their patriarchal, witchcraft obsessed, horticultural neighbours really shape those societies and generate totally the starkly different values, and ideologies and relationships toward nature that you find in those cultures, which subsequent research has supported.

Anyhow, the authors continue:

“Before long, it was simply assumed by almost everyone that foragers represented a separate stage of social development, that they ‘live in small groups’, ‘move around a lot’, reject any social distinctions other than those of age and gender, and resolve conflicts by ‘fission’ rather than arbitration or violence.35”

And of course the authors neglect to mention just how egalitarian these societies are, including gender egalitarianism, and just how important of a revelation that was at the time, and still is.

“The fact that these African societies were, in some cases at least, refugee populations living in places no one else wanted, or that many foraging societies documented in the ethnographic record (who had by this time been largely wiped out by European settler colonialism and were thus no longer available for quantitative analysis) were nothing like this, was occasionally acknowledged. But it was rarely treated as particularly relevant. The image of tiny egalitarian bands corresponded perfectly to what those weaned on the legacy of Rousseau felt hunter-gatherers ought to have been like. Now there seemed to be hard, quantifiable scientific data (and also movies!) to back it up”

OK, now this is just shameful – remember how I mentioned earlier, that once the news about hyperegaltiarian socieites made it out into the word, the miserable cynics and right wingers who hate the idea that humans could ever be egalitarians flipped their lids and did everything they could to start attacking and downplaying everything about hunter gatherer egalitarianism?

Well that whole paragraph comes straight out of that anti-egalitarian miserable asshole talking points playbook!

The thing about hyperegalitarian foragers being refugees comes from the so called “Kalahari debate” from the late 80’s and early 90s where a group of scholars centred around Edwin Wilmsen and James Denbow, tried to reject just about everything that anthropologists had been writing about the various Kalahari hyper egalitarian hunter gatherers since the Man the Hunter conference. According to these revisionist scholars, far from having anything to teach us in terms of how our ancestors lived, or in terms of the potential for human egalitarianism and liberty, the Kalahari bushmen were actually just a bunch of sad losers.

Not only were they not at all the “original affluent society” that hunter gather specialists had been depicting, who enjoyed both equality and freedom thanks to their ancient foraging economy, but they weren’t ancient, they weren’t egalitarian, they weren’t real foragers, and they weren’t even a real society!

According the revisionists, the only reason that bushmen were equal was that they were the equally oppressed lower loser classes of a larger society of pastoralists and farmers. And the only reason that they were foragers was because they had been forced to abandon pastoralism by stronger ethnic groups who had stolen all of their cattle and shoved them into a crappy wasteland. Far from being a society that we can learn from, both their hunting and gathering economy and their equality were signs of degradation and subjugation – something Turgot would have loooved. And all of this was being obscured by the evil sin of categories!

With a peculiar mix of self-righteousness and cynicism, these scholars portrayed themselves as advanced realists and anti-racists, crusading against the “essentialism” of the supposed fantasy world created by hunter gatherer specialists. And the underlying political message coming from these scholars was that categories are bad and that human equality is some kind of rare marginal phenomenon that didn’t play a big role in human history. In other words, hierarchy and exploitation and misery are the norm of the human species. Jordan Peterson and Praeger U can breathe a sigh of relief.

Unsurprisingly, most of these revisionist scholars have ended up on the wrong side of the more recent so-called “indigenous peoples’ debate” where they are not just rejecting the category of indigenous societies, but also have also been straight up supporting the eviction of kalahari bushmen and other peoples from their hunting lands, thereby supporting the destruction of these societies and their way of life in the in the name of progress development.

Now there is a ton of literature on the kalahari debating these claims back and and forth since the late 1980s – but some reason Graeber and Wengrow don’t cite anything to back up their statement about these people being refugees.

Maybe it’s because the people who see the bushmen as a real culture basically won that debate over time – a big chunk of the revisionist argument was based on Wilmsen misreading the word “onions” as “oxen” in an old diary which led him to mistakenly that the Bushmen used to have cattle until recent times – or maybe because it’s because if you read any of the back and forth you’ll see that this it looks like something of a left vs right debate between people who think that equality is impossible and those who think that it is possible, and the authors of Dawn of Everything are championing the politically wrong side of that argument… or maybe they just forgot, who knows.

Now, the whole thing about hunter gatherers living on territories that historically nobody else wants, like savannahs or rainforests or deserts is certainly true – hunter gatherers are generally militarily weaker than pastoralist or agricultural societies because their population densities are so low, so they get easily displaced. But just because a territory is unsuitable for farming or pastoralism, or agriculture, doesn’t mean that it’s not a good foraging habitat, and every book about these societies by experts will remark on how the forager groups are better fed and live a more enjoyable lifestyle than their farmer and pastoralist neighbours, even when they’re stressed for resources – right up until they get pushed out of foraging by capitalism or civil war or encroachment by militarily stronger societies – which is sadly the case now with the kalahari foragers, who are no longer full time foragers as of the past few ten years or so. And I’ll link to an article specifically addressing the quality of environment issue in the bibliographhy.

The authors continue:

“In this new reality, Lévi-Strauss’s Nambikwara were simply irrelevant. After all, in evolutionary terms they weren’t even really foragers, since they only roamed about in foraging bands for seven or eight months a year. So the apparent paradox that their larger village settlements were egalitarian while their foraging bands were anything but could be ignored, lest it tarnish this crisp new picture. The kind of political self-consciousness which seemed so self-evident in Nambikwara chiefs, let alone the wild improvisation expected of Nuer prophets, had no place in the revised framework of human social evolution.”

Another total garbage paragraph.

Even if Levi-Strauss hadnt messed up about the nambikwara having two separate modes of subsistence – there’s no reason why the Nambikwara be relevant to what our early ancestors were doing? Our early ancestors weren’t doing farming for 5 months of the year or any months of the year. There are dozens of other societies that we’d want to look at for insights into our origins before we looked at the Nambikwara. But then again, Graeber and Wengrow think that we can generalize about our african first ancestors from 300 000 years ago by going on about gobleki tepe and about the european ice age people who lived on the fringes of human habitability in totally different circumstances – so wheee anything goes.

So to summarize this section – while the Nambikwara are certainly interesting, the entire section on them in this book is just a giant waste of made up garbage on top of made up garbage on top of giant mistakes, and bullshit strawmen that don’t teach us anything about anything besides what really bad scholarship looks like. Please send me money to compensate me for all the time I wasted figuring this out!

OUT COME THE FREAKS

Anyhow, from this complete waste of a section, the authors then go on to talk about societies that actually do change their social structures in terms of relative hierarchy or equality in different seasons, in particular the artcit inuit and the kwakiutl or kwakwakawakw as they’re properly called, of the pacific northwest coast.

Whereas earlier in the chapter, the authors tried to tell us that the rich burials of upper palaeolithic europe teach us that inequality has no origin – which implies that they are evidence of social hierarchy – in this part of the chapter, the authors tell us the opposite – that these burials actually are not evidence of hierarchy at all – they’re just ritually celebrated freaks with unusual bodies or birth defects who come from societies that had seasonal variations where people were dispersed into hunting groups part of the year, and then congregated en masse for another part of the year – like the fictionalized version of the Nambikwara that they just described.

“Let’s return to those rich Upper Palaeolithic burials, so often interpreted as evidence for the emergence of ‘inequality’, or even hereditary nobility of some sort. For some odd reason, those who make such arguments never seem to notice – or, if they do, to attach much significance to the fact – that a quite remarkable number of these skeletons (indeed, a majority) bear evidence of striking physical anomalies that could only have marked them out, clearly and dramatically, from their social surroundings.

“The adolescent boys in both Sunghir and Dolní Věstonice, for instance, had pronounced congenital deformities; the bodies in the Romito Cave in Calabria were unusually short, with at least one case of dwarfism; while those in Grimaldi Cave were extremely tall even by our standards, and must have seemed veritable giants to their contemporaries.

“All this seems very unlikely to be a coincidence. In fact, it makes one wonder whether even those bodies, which appear from their skeletal remains to be anatomically typical, might have been equally striking in some other way; after all, an albino, for example, or an epileptic prophet given to dividing his time between hanging upside down and arranging and rearranging snail shells would not be identifiable as such from the archaeological record.

“It seems extremely unlikely that Palaeolithic Europe produced a stratified elite that just happened to consist largely of hunchbacks, giants and dwarfs.

“There are any number of other interpretations that could be placed on the evidence – though the idea that these tombs mark the emergence of some sort of hereditary aristocracy seems the least likely of all.

So the authors see these rich burials not as evidence of hierarchy, but of something like Nuer prophets. Anomalous people that are given some kind of special status as a result of their strangeness.

And then they tie it in to seasonality:

“Almost all the Ice Age sites with extraordinary burials and monumental architecture

And rememeber that we saw last time that they just made this up – there are precisely ZERO ice age sites with monumental architecture!

“these sites – were created by societies that lived a little like Lévi-Strauss’s Nambikwara, dispersing into foraging bands at one time of year, gathering together in concentrated settlements at another.

Which we just saw isn’t true

> This seems to be the explanation for those hubs of activity found in eastern Europe at places like Dolní Věstonice where people took advantage of an abundance of wild resources to feast, engage in complex rituals and ambitious artistic projects, and trade minerals, marine shells and furs.

> Archaeology also shows that patterns of seasonal variation lie behind the monuments of Göbekli Tepe.”

Which, remember was built in the holocene era that we live in now – not in the ice age. And then they talk about how stonehenge was built by people who abandoned farming to do foraging and pastoralism, which they act like that’s supposed to be some kind of game changing big deal, and how those people had a seasonal structure too – which OK, great – stonehenge was built 5000 years ago by neolithic pastoralists, so I have no idea what that has to do with anything.

If you read carefully, you see that just like the earlier part about paleolithic inequality, this whole section is a lot of smoke and mirrors – like what do nuer prophets or palaeolithic dwarves or albinos have anything to do with seasonal social structures?

The authors are painting a picture that suggests that during seasonal sedentary camps, people in the european ice age and throughout human history and prehistory engaged in rituals where we worshipped freaks and had play hierarchies – so we were always hierarchical and egalitarian on and off. And I say play hierarchies because this is how they characterize them towards the end of the chapter as we’ll see.

But Nuer prophets were totally unrelated to nuer seasonal patterns. kwakiutl and inuit had pronounced seasonal settlement and social patterns, but they didn’t have special seasonal leaders and they didn’t revere freaks.

The palaeolithic freaks theory might be valid, but there’s literally no connection whatsoever to the Nuer or the Inuit or Kwakiutl.

Anyways, then they connect the palaeolithic european societies to the Inuit and to the authors’ dumb thesis that social structure is a discombobulated conscious choice

> Recall that for Lévi-Strauss, there was a clear link between seasonal variations of social structure and a certain kind of political freedom. The fact that one structure applied in the rainy season and another in the dry allowed Nambikwara chiefs to view their own social arrangements at one remove: to see them as not simply ‘given’, in the natural order of things, but as something at least partially open to human intervention.

And of course Levi-Strauss says absolutely nothing of the sort – just like they did with Christopher Boehm last time, the authors are turning Levi-Strauss into a muppet and making him say things he never said.

And they continue:

“Writing in the midst of the Second World War, Lévi-Strauss probably didn’t think he was saying anything all that extraordinary. For anthropologists in the first half of the twentieth century, it was common knowledge that societies doing a great deal of hunting, herding or foraging were often arranged in such a ‘double morphology’ (as Lévi-Strauss’s great predecessor Marcel Mauss put it).43 Lévi-Strauss was simply highlighting some of the political implications.”

that’s correct – he wasn’t saying anything super extraordinary, then or now, that article is only interesting in terms of the psychology of the chief, which is what it’s about.

“But these implications are important. What the existence of similar seasonal patterns in the Palaeolithic suggests is that from the very beginning, or at least as far back as we can trace such things, human beings were self-consciously experimenting with different social possibilities. It might be useful here to look back at this forgotten anthropological literature, with which Lévi-Strauss would have been intimately familiar, to get a sense of just how dramatic these seasonal differences might be”

So, where the authors were making shit up about the Nambikwara and wasting my life, here they do come up with actual examples of seasonal variations in the level of hierarchy and equality of a society, and there is a lot we can learn from this – if we focus on all of the things that Graeber and Wengrow choose to consistently ignore:

> The key text here is Marcel Mauss and Henri Beuchat’s (1903) ‘Seasonal Variations of the Eskimo’. The authors begin by observing that the circumpolar Inuit ‘and likewise many other societies … have two social structures, one in summer and one in winter, and that in parallel they have two systems of law and religion’.

“In the summer, Inuit dispersed into bands of roughly twenty or thirty people to pursue freshwater fish, caribou and reindeer, all under the authority of a single male elder.

“During this period, property was possessively marked and patriarchs exercised coercive, sometimes even tyrannical power over their kin – much more so than the Nambikwara chiefs in the dry season. But in the long winter months, when seals and walrus flocked to the Arctic shore, there was a dramatic reversal. Then, Inuit gathered together to build great meeting houses of wood, whale rib and stone; within these houses, virtues of equality, altruism and collective life prevailed. Wealth was shared, and husbands and wives exchanged partners under the aegis of Sedna, the Goddess of the Sea.4

OK, so most of this is accurate, except that I have no idea where they get the part about summer bands being organized around 20-30 people under a single male leader – it’s definitely not in the book they’re referencing, and I tried looking elsewhere but didn’t see anything but I wasted so much time on the nambikwara that I didn’t want to waste more time on this – so maybe it is true, or maybe they made it up, and if you know the answer feel free to let me know.

In any case what Mauss actually says about summer settlement size is that:

“From one end of the Eskimo area to the other, this group [meaning the settlement] consists of a family, defined in the narrowest sense of this word: a man and his wife (or, if there is room, his wives) plus their unmarried children … In exceptional cases, a tent may include an older relative, or a widow who has not remarried and her children, or a guest or two.

And these aren’t settlements made up of individual families, the settlements are just isolated individual families “located at a considerable distance from one another.”

but anyhow, the authors continue:

“Mauss thought the Inuit were an ideal case study because, living in the Arctic, they were facing some of the most extreme environmental constraints it was possible to endure.

“Yet even in sub-Arctic conditions, Mauss calculated, physical considerations – availability of game, building materials and the like – explained at best 40 per cent of the picture. (Other circumpolar peoples, he noted, including close neighbours of the Inuit facing near-identical physical conditions, organized themselves quite differently.) To a large extent, he concluded, Inuit lived the way they did because they felt that’s how humans ought to live.

Ooh 40% – that’s a very specific number. It’d be interesting to see how Mauss got at that figure. Did he do some kind of data analysis, or was that just a sort of guesstimate? Let’s do a deep dive and find out…

So, if you read the book they’re referring to … drumroll …. Mauss never says anything about 40% of anything, ever! Just straight up making shit up, again. Hey Bert, I made up some numbers bert! 69 Bert!

Not only that, but more importantly, Mauss basically says the exact opposite of what the authors are saying here.

What Mauss actually says, sounding like a proto-behavioural ecologist, is that the seasonal differences between the Inuit’s social organization and cultural practices are almost entirely explained by material conditions – specifically the migration patterns of the animals that they hunt!

“We must look to the Eskimo way of life for the causes of this situation [meaning their dual settlement patterns and cultural social structure]. Indeed, this is not at all difficult to understand; it is, on the contrary, a remarkable application of the laws of biophysics and of the necessary symbiotic relation among animal species.

“European explorers have frequently insisted that, even with European equipment, there is no better diet nor better economic system in these regions than that adopted by the Eskimo. They are governed by environmental circumstances.

“In summary, summer opens up an almost unlimited area for hunting and fishing, while winter narrowly restrictsb this area.10 This alternation provides the rhythm of concentration and dispersion for the morphological organization of Eskimo society. The population congregates or scatters like the game. The movement that animates Eskimo society is synchronized with that of the surrounding life.

The only thing that Mauss points to that animal migration patterns don’t explain is why the Inuit choose to specifically live in multifamily igloos instead of living in separate houses in the winter, and why they build assembly houses, which the authors ludicrously called “monumental architecture” when referring to the palaeolithic versions of these types of small buildings.

“The natives could have placed their tents side by side .. or they could have constructed small houses instead of living in family groups under the same roof. One ought not to forget that the kashim, or men’s house, and the large house where several branches of the same family reside are not confined to the Eskimo. They are found among other peoples and, consequently, cannot be the result of special features unique to the organization of these northern societies.

“They have to be related, in part, to certain characteristics that Eskimo culture has in common with these other cultures.

And Mauss doesn’t say that other circumpolar people were organized quite differently. He does say that some Inuit had contact with Athabascans and Algonquins as trading partners and that the Inuit would have benefitted from adopting Athabascan snowshoes instead of the waterproof boots that they used, but that they refused to do so – schizmogenesis? But he doesn’t say anything about Algonquin or athabascan social organization one way or the other and the Algonquins don’t live in the artic at all, and athabastans lived in alaska in different circumstances, hunting different animals, with different seasonal rhythms, so again, all of this is just totally fake news.

So that’s 2 cultures out of 2 so far where Graeber and Wengrow seem to have just been making a bunch of shit up about.

Then the authors talk about the cultural and legal differences from summer to winter

“… many aspects of winter life … reversed the values of summer. In the summer, for instance, property rights were clearly asserted and sometimes physically inscribed onto personal objects, especially hunting weapons. But in the communalistic atmosphere of the winter house, generosity trumped accumulation as a route to personal prestige. The right of male patriarchs to coerce their sons (and indeed the group as a whole) was acknowledged only in the summer months. It had no place around the winter hearth, where the principles of Inuit leadership were turned on their head. Legitimate authority became a matter of charisma rather than birthright; persuasion instead of coercion.

And another important change from season to season that Mauss discusses, but that Graeber and Wengrow didn’t get into, is that the inuit barely had any religious life in the summer, and they don’t really observe many taboos or rituals. But in the winter they have a rich religious and ritual life with many rules to be observed.

So then the authors argue that all of these seasonal difference are because of conscious choice and awareness of different political possibilities, blah, blah, which of course Mauss doesn’t say anything at all about in his book.

So how can we better explain these important cultural differences from season to season, and what does Mauss have to say about them?

While Mauss tells us that the dual social structure of the Inuit is the result of the seasonal dispersal patterns of the animals that they hunt, he doesn’t give us any specific reasons for how that translates into patriarchy and private property in one season vs gender equality and communalism in the other season. So let’s use our materialist trained noggins to see what we can figure out.

So remember, that according to Mauss the inuit all congregate together in winter because the seals and walrus they hunt are all clustered in one area each year.

And in the summer they separate into individual families, because the animals that they hunt and the foods they gather are widely dispersed.

This give us the information that we need to figure out some pretty parsimonious answers as to what’s going on:

So for example property relations – why was there more private property in the summer vs more communal property in the winter:

Hunting and fishing in summer were mostly an individual affair. So you have your individual stuff, and there’s nobody to really share it with, except for your immediate family.

In the winter hunting is communal, so people depend on eachother and share their catches and use eachothers’ property. And that’s when they make all their social connections. And there are lots of people around who you want to maintain good relations with, and also who have leverage to pressure you into sharing with them – so there’s are many more reasons and incentives to share, and people to share with vs in the very isolated and lonely summer season.

What about religion?

While some religions like western protestantism are more of an individual affair, in most traditional societies religion is largely a communal affair, and it’s often more about establishing different kinds of social relations and ties, and values and boundaries than about actual beliefs.

You don’t really need as many practices and rituals if you’re just with your family. Anyone who’s done an elaborate 3 hour passover seder when a lot of different guests are present with songs, and readings, and spraying wine and throwing rubber frogs at everyone, vs the five minute version with just mom and dad and siblings knows what I’m talking about.

And how do inuit settlement patterns explain differences in gender relations?

The authors want us to believe that the inuit consciously understood that they had many social possibilities and that they chose patriarchy in the summer and equality in the winter, as opposed to us who are stuck.

Well, here’s a description of inuit gender relations from a book called Inuit Women by Janet Mancini Bilson and Kyra Mancici

“Life was hard for the Inuk woman, as one elder recalls: “She was the first to rise and the last to sleep. Her husband was always right—she could be punished by her parents for not pleasing her husband.” In terms of power distribution, the husband was clearly the head of the family: “He had the final word, and that’s just the way it was.” The Inuit tended to accept the principle of ultimate male authority, as an elder recalls: “The man was the boss . . . all the men.”

Now this sounds to me like women were actually pretty stuck in gender hierarchy during the summer.

Did women consciously choose this situation over and over every single summer because it’s some fun and kinky SM game to play subservient wife, or because of some random Inuit values that just emerge from the mysterious extraterrestrial inuit mind?

Obviously not – men imposed this on women, and women tolerated it. So what are the conditions that gave men the advantage to be able to impose this on women in the summer but not in winter?

Remember the two criteria for hierarchy: control over resources and having no better alternatives to access those resources.

Well, in the summer, women are in single family units where they are almost entirely dependent for survival on father and brothers who do all the hunting. And father and brothers are probably physically stronger than they are on top of that, and they’re hoarding their hunting weapons as private property not to he shared with their wives. Private property in this case is most likely a concommitant of gender hierarchy!

Meanwhile tents are a large distance from one another in summer, so it’s hard to escape and there isn’t really any great place to escape to. Since everyone is busy feeding their immediate families and chasing very dispersed resources, it’s a significant imposition to suddenly show up at your brother’s house and be another mouth to feed, so that everyone gets 15-20% less food thanks to you.

In other words, the conditions inherent to the economic activities of summer put men at a general bargaining power advantage vis à vis women.

Now, women still had a decent amount of bargaining power and Bilson and Mancini point out that men could not survive without female labour either. So if need be, a woman could play a dangerous game of brinksmanship to get concessions out of men – but a lot of cultural norms specifically exist to avoid these chaotic and dangerous power struggles which can end in catastrophe for the winners as well as the losers.

That’s why a woman’s parents would punish her for being disobedient – because in the long run it could mean death for her and her kids and her husband as well.

If there’s a physical fight, the man will likely win. But it’s extremely dangerous to ever let it get anywhere near that point when you’re all alone for several months with only your immediate family. That’s why inuit culture is famously extremely averse to any expressions of anger, even moreso than other hunter gathers many of whom share that same cultural trait. See Jane Briggs book Never in Anger.

And contrary to the idea of conscious choice, the whole point of cultural rules is usually to avoid conscious choices, to avoid individuals making calculations that might seem like they’re in your short term interest, but that will doom you or the wider group in the long run.

Think about Kosher laws against eating swine. Marvin Harris noticed that laws against eating swine exist not in the middle east among Jews and Muslims, but also in other regions around the world. And what these cultures share in common is that in those areas, it’s only possible to feed pigs with the same foods that humans eat.

If only some people raise pigs, or if it’s a good harvest year, raising pigs is a great idea to improve your farmer diet. But but once everyone starts to do it, or when harvests are bad, suddenly you end up with massive food shortages, and starvation and class war between pig owners and non pig owners and chaos and social collapse.

If you depend on peoples’ individual rational choices, then everyone will want to raise pigs, even even they know that it might kill them in the long run. So it’s more effective to make it a deeply ingrained religious and social taboo where the actual cause is obscured and people just don’t even consider it in the first place because the whole idea of eating pigs just makes you supernaturally horrified.

So after a few rounds of pig caused famines, people in these areas developed these taboos. Just like Inuit must have developed patriarchal values after repeated power struggles causing chaos. Over time, as a result of some of these battles, the values of the society end up reflecting the balance of power of the society, determining the winner in advance in order to avoid constant battles.

Meanwhile, in the winter, the inuit lived in multifamily homes in large settlements with many homes close together. This means that both men and women had their relatives around – and women in particular had male relatives around. This means that if anyone tried to bully a women, her brothers and father and uncles would have something to say about it. Also any woman will likely have close relatives and friends around that she can move in with if she wants to get a way from her husband or divorce him.

I think that these explanations are much more parsimonious and insightful than decontextualized “conscious choice” and “experimenting with social possibilities”.

LAKOTA BUFFLO HUNT

Now the authors move south from the arctic to the great plains of north america

“Plains nations were one-time farmers who had largely abandoned cereal agriculture, after re-domesticating escaped Spanish horses and adopting a largely nomadic mode of life.

The authors continue, discussing the observations of early 20th century anthropologist Robert Lowie

“In late summer and early autumn, small and highly mobile bands of Cheyenne and Lakota would congregate in large settlements to make logistical preparations for the buffalo hunt. At this most sensitive time of year they appointed a police force that exercised full coercive powers, including the right to imprison, whip or fine any offender who endangered the proceedings. Yet, as Lowie observed, this ‘unequivocal authoritarianism’ operated on a strictly seasonal and temporary basis. Once the hunting season – and the collective Sun Dance rituals that followed – were complete, such authoritarianism gave way to what he called ‘anarchic’ forms of organization, society splitting once again into small, mobile bands. Lowie’s observations are startling:

[and here they quote Lowie]

“”In order to ensure a maximum kill, a police force – either coinciding with a military club, or appointed ad hoc, or serving by virtue of clan affiliation – issued orders and restrained the disobedient. In most of the tribes they not only confiscated game clandestinely procured, but whipped the offender, destroyed his property, and, in case of resistance, killed him. The very same organisation which in a murder case would merely use moral suasion turned into an inexorable State agency during a buffalo drive. However … coercive measures extended considerably beyond the hunt: the soldiers also forcibly restrained braves intent on starting war parties that were deemed inopportune by the chief; directed mass migrations; supervised the crowds at a major festival; and might otherwise maintain law and order.46

Back to Graeber and Wengrow:

“During a large part of the year,’ Lowie continued, ‘the tribe simply did not exist as such; and the families or minor unions of familiars that jointly sought a living required no special disciplinary organization. The soldiers were thus a concomitant of numerically strong aggregations, hence functioned intermittently rather than continuously.’ But the soldiers’ sovereignty, he stressed, was no less real for its temporary nature. As a result, Lowie insisted that Plains Indians did in fact know something of state power, even though they never actually developed a state.

In other words the reason you had a police force part of the year, but then no enforcement of even murder for the rest of the year is not because of random conscious choices about political possibilities, but because during the buffalo hunt, you aggregated in big enough numbers to actually have a force capable of enforcing rules. As lowie says – the tribe simply did not exist for much of the rest of the year as people were dispersed into small groups to pursue seasonally dispersed resources – somewhat similar to the inuit but with larger small bands not just isolated families.

I’m suspicious of Lowie saying that small bands didn’t require disciplinary organization – the fact that Lowie talks about a murder case being dealt with moral suasion suggests to me that they did need discipline, but that you had no one to enforce it. In a small band setting, it becomes really dangerous to punish or kill someone, even a murderer, because it can turn into a feud and destroy your ability to survive. This is why most hunting and gathering societies have strict rules about anger and violence. People would like to control murderers during the off season, but they can’t do it effectively.

In his article Lowie compares this seasonal change to the season changes of the inuit as described by Mauss, and like Mauss, Lowie attributes social change to economic and logistical factors, and not Graebgrow’s shroom hyper consciousness.

The authors continue, writing as if this stuff breaks the mold of strawman anthropology:

“It was confusing enough that people like the Nambikwara seemed to jump back and forth, over the course of the year, between economic categories.

“The Cheyenne, Crow, Assiniboine or Lakota would appear to jump regularly from one end of the political spectrum to the other. They were a kind of band/state amalgam. In other words, they threw everything askew.

> Scholarship does not always advance. Sometimes it slips backwards. A hundred years ago, most social scientists understood that those who live mainly from wild resources were not normally restricted to tiny ‘bands’. As we’ve seen, the assumption that they were only gained ground in the 1960s.

Ugh – There are zillions of articles discussing all the different types of hunter gatherers with different kinds of social organiztion – see Robert Kelley’s book The Foraging Spectrum originally written in 1995 and last updated in 2014 – and articles debating the implications of hierarchical vs egalitarian hunter gatherers, on what life was like for our early ancestors. It’s a huge literature that Graeber and Wengrow seem to have no curiosity about.

It is true that in the 1960s people paid less attention to non egalitarian foragers or less egalitarian foragers, because everyone was so excited about discovering the existence of hyper-egalitarian foragers, and by the very hopeful and inspiring possibility that humanity may have egalitarian origins and that we might be best suited to live in egalitarian societies.

The authors continue:

> Since in this new, evolutionist narrative ‘states’ were defined above all by their monopoly on the ‘legitimate use of coercive force’, the nineteenth-century Cheyenne or Lakota would have been seen as evolving from the ‘band’ level to the ‘state’ level roughly every November, and then devolving back again come spring. Obviously, this is silly. No one would seriously suggest such a thing. Still, it’s worth pointing out because it exposes the much deeper silliness of the initial assumption: that societies must necessarily progress through a series of evolutionary stages to begin with. You can’t speak of an evolution from band to tribe to chiefdom to state if your starting points are groups that move fluidly between them as a matter of habit.

Again, what’s silly is pretending that anthropologists from the 1960s and 70s were time-warped from the 1860s and 70s. A social evolutionist would not be freaked out by the lakota police, they’d be interested in thinking about whether or not that type of institution might eventually get “stuck” and turn into an authoritarian system and, they’d be wondering if some authoritarian chieftainships we’ve seen in recent times might have had their origins in this type of institution in the past, and Lowie actually talks about this briefly.